The device

The obi product is a revolutionary patent-pending device that brings together advanced sample collection, processing, and analysis into a single, user-friendly system. Designed for broad health applications, the device can analyze a range of biological markers, including hormones and other key analytes, with high accuracy.

The assay

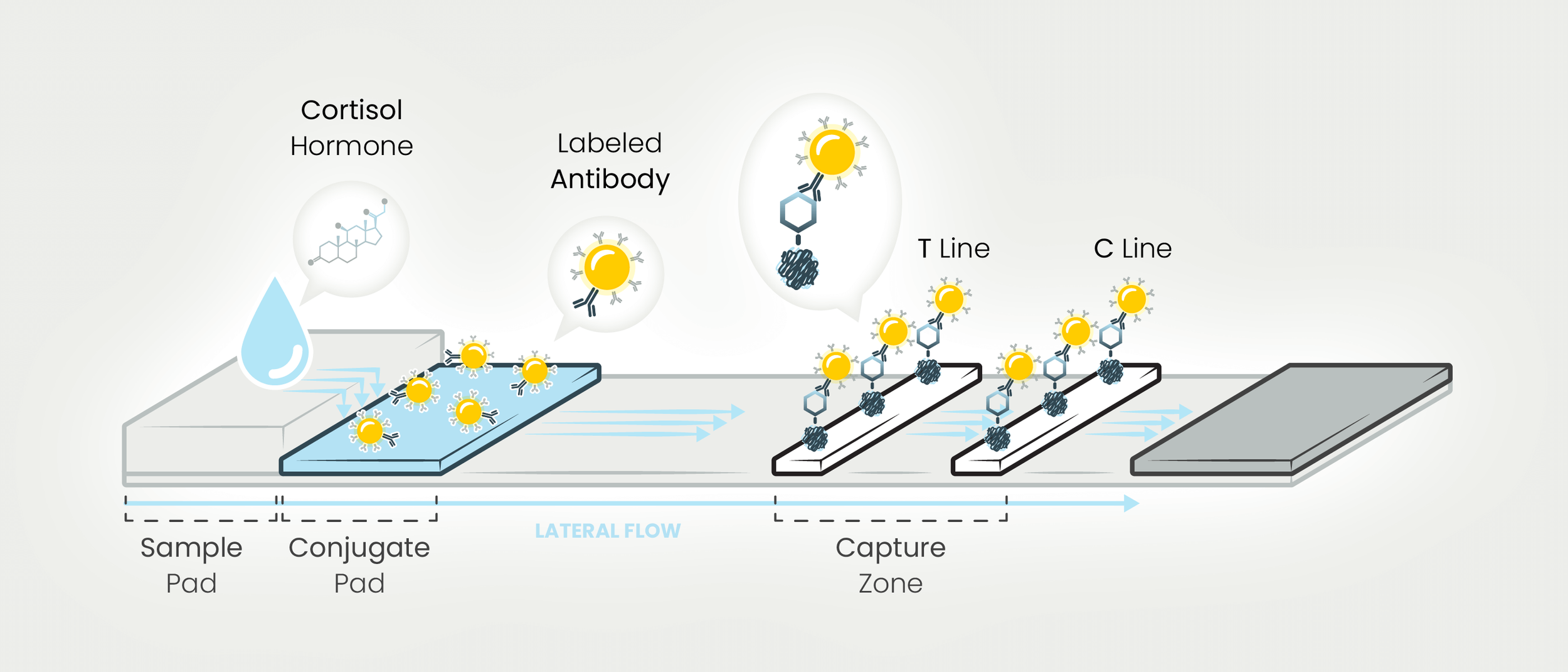

obi uses lateral flow assay (LFA) technology to detect salivary cortisol. LFAs are simple devices that identify substances in liquid samples without costly equipment. The obi assay operates on competitive binding: cortisol in saliva competes with immobilized cortisol on the test strip for binding to labeled antibodies. Higher cortisol levels result in a fainter test line, while lower levels create a more visible line. A control line ensures proper function. LFAs are widely used due to their simplicity, speed, and affordability.

The results

obi provides a clear visual representation of cortisol levels within 20 minutes, categorized as low, medium, or high. These three levels were defined using data from over 100,000 saliva samples in the CIRCOT database and help determine if your levels fall outside the normal range for both morning and night testing.

The analyte

Cortisol, primarily known for its role in the "fight or flight" response, regulates processes like blood pressure, glucose levels, metabolism, and the sleep-wake cycle. It follows a diurnal rhythm, peaking in the morning and dropping throughout the day. However, stress, poor diet, and lack of sleep can disrupt this cycle. Chronically abnormal cortisol levels are linked to anxiety, depression, fatigue, high blood pressure, weight gain, weakened immunity, and increased risks of heart disease and diabetes.

The research

American Psychological Association. (2013, January 1). How stress affects your health. http://www.apa.org/topics/stress/health

Armani Kian, A., Vahdani, B., Noorbala, A. A., Nejatisafa, A., Arbabi, M., Zenoozian, S., & Nakhjavani, M. (2018). The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Emotional Wellbeing and Glycemic Control of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of diabetes research, 2018, 1986820. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1986820

Björntorp, P., & Rosmond, R. (2000). Obesity and cortisol. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 16(10), 924–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00422-6

Chandola, T., Brunner, E., & Marmot, M. (2006). Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: prospective study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 332(7540), 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38693.435301.80

Dmitrieva, N. O., Almeida, D. M., Dmitrieva, J., Loken, E., & Pieper, C. F. (2013). A day-centered approach to modeling cortisol: diurnal cortisol profiles and their associations among U.S. adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(10), 2354–2365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.003

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

Hormone Health Network."Cortisol | Hormone Health Network." Hormone.org, Endocrine Society, 22 April 2021. Cortisol | Hormone Health Network

Krieger D. T. (1975). Rhythms of ACTH and corticosteroid secretion in health and disease, and their experimental modification. Journal of steroid biochemistry, 6(5), 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4731(75)90068-0

Lloyd, C., et al. “Stress and Diabetes: A Review of the Links.” Diabetes Spectrum Apr 2005, 18 (2) 121-127; DOI: 10.2337/diaspect.18.2.121. 0121.qxd (diabetesjournals.org)

Mayo Clinic Staff. “Stress symptoms: Effects on your body and behavior.” Stress management, 4 April 2019. Stress symptoms: Effects on your body and behavior - Mayo Clinic

McEwen B. S. (2008). Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. European journal of pharmacology, 583(2-3), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071

Riediger, N. D., Othman, R. A., Suh, M., & Moghadasian, M. H. (2009). A systemic review of the roles of n-3 fatty acids in health and disease. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(4), 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.022

Torres, S. J., & Nowson, C. A. (2007). Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 23(11-12), 887–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Stress and your health.” Office on Women’s Health, March 2019. Stress and your health | Office on Women's Health (womenshealth.gov)

Van Eck, M., Berkhof, H., Nicolson, N., & Sulon, J. (1996). The effects of perceived stress, traits, mood states, and stressful daily events on salivary cortisol. Psychosomatic medicine, 58(5), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199609000-00007

Vining, R. F., McGinley, R. A., Maksvytis, J. J., & Ho, K. Y. (1983). Salivary cortisol: a better measure of adrenal cortical function than serum cortisol. Annals of clinical biochemistry, 20 (Pt 6), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/000456328302000601

Vining, R. F., McGinley, R. A., & Symons, R. G. (1983). Hormones in saliva: mode of entry and consequent implications for clinical interpretation. Clinical Chemistry, 29(10), 1752–1756. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/29.10.1752

Whitworth, J. A., Williamson, P. M., Mangos, G., & Kelly, J. J. (2005). Cardiovascular consequences of cortisol excess. Vascular health and risk management, 1(4), 291–299. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147%2Fvhrm.2005.1.4.291

Gavrieli A, Yannakoulia M, Fragopoulou E, et al. Caffeinated coffee does not acutely affect energy intake, appetite, or inflammation but prevents serum cortisol concentrations from falling in healthy men. J Nutr 2011;141(4):703-707.

Ohlsson C, Nethander M, Kindmark A, et al. Low serum DHEAS predicts increased fracture risk in older men: The MrOS Sweden Study. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32(8):1607-1614.

Ponzetto, F., Settanni, F., Parasiliti-Caprino, M. et al. Reference ranges of late-night salivary cortisol and cortisone measured by LC–MS/MS and accuracy for the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 43, 1797–1806 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01388-1